|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Medicine and Art: Imagining a Future for Life and Love

Lucy Birmingham |

|

|

|

|

Gilles Barbier, "L'Hospice / The Nursing Home" (2002); six wax figures, television, various elements

Photo by Martin Z. Margulies, Miami, USA

Courtesy of Galerie G.-P. & N. Vallois, Paris |

|

Maruyama Okyo, "Skeleton Performing Zazen on Waves" (c.1787); ink, paper

Courtesy of Daijoji temple, Hyogo, Japan |

|

|

|

|

Art meets medicine in weird and wonderful ways that have questioned and illuminated medical advances throughout history. From Leonardo da Vinci's exploratory drawings of a dissected human head to bio-artist Eduardo Kac's genetically engineered fluorescent bunny "Alba," artists have developed their styles and techniques both in parallel to and in advance of scientific and medical discoveries with beauty, shocking panache, humor and profound insight.

An in-depth look at this extraordinary synergy is now on view until February 28 at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, in an exhibition titled Medicine and Art: Imagining a Future for Life and Love -- Leonardo da Vinci, Okyo, Damien Hirst. It's a pioneering show for Japan, and for much of the world. Visitors are reacting with a mix of revulsion, curiosity and awe.

About 150 works are from the renowned U.K.-based Wellcome Collection. They are a small sampling from the vast collection of bizarre and wondrous medical artifacts amassed by the American-British pharmaceutical entrepreneur and philanthropist Sir Henry Wellcome (1853-1936).

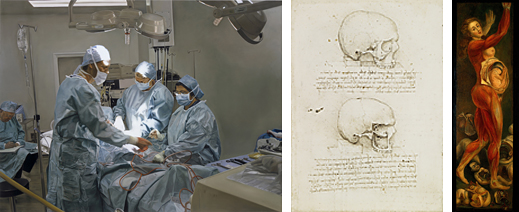

Many of the older paintings and etchings from the collection are beautiful renditions of gut-wrenching dissections. Far from the stark images in modern-day medical books, these classical works bridge art and medicine with painterly form. In Jacques-Fabian Gautier d'Agoty's "Dissection of a Pregnant Female Figure, Lateral View 1764-1765," the pretty-faced model smiling brightly at us reveals a cut-open abdomen large with child.

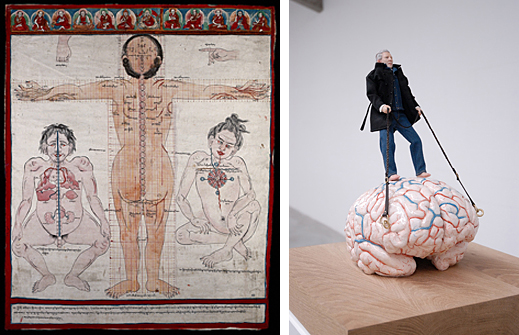

Three of Leonardo da Vinci's precious anatomical drawings from 1489 and 1508, loaned from the Royal Collection of the British Royal Family, are on display for the first time in Japan. Two are of human skulls and the third is the brain of an ox. Leonardo performed more than 30 dissections in a quest to learn about the "micro-cosmos of the human body" and the "macro-cosmos of the whole universe." Like contemporary sculptors of his time, he used a molten wax casting method that revealed the interior connections of the cranium and brain.

|

left: Three Tibetan Anatomical Figures (c.1800); watercolor and black ink on white linen

Courtesy of Wellcome Library

right: Jan Fabre, "Ik men mijn eigen brein II (I Drive My Own Brain II)" (2008); paint on medical silicone, wax, textiles, leather and metal

Courtesy of DEWEER gallery, Otegem, Belgium

Photo by Dirk Pauwels / DEWEER gallery, Otegem, Belgium; © Angelos

|

Also in the exhibition are 30 works by contemporary artists, including Damien Hirst and some of Japan's rising art stars such as sculptor Tetsuya Noguchi, photographer Mika Ninagawa, Nihonga painter Fuyuko Matsui and multi-media artist Miwa Yanagi. Yanagi's "The Three Fates" (2008) was inspired by the Three Fates or Moirae in Greek mythology who controlled the "threads of life." The two large digital prints of the goddesses as tantalizing youth and decrepit hags explore the realm of aging, life and death.

Throughout the exhibition, death appears omnipotent as both friend and foe. One of the most impactful examples of this is Walter Schels's "Life Before Death" (2003-2005), a series of black and white photo portraits of adults and one baby, close to and just after death. Placing the viewer literally in the face of death, the oversized images are jolting, but at the same time tender and strangely reassuring. In contrast to the gaping dissections on view in the other rooms, they show that life could end gently with eternal sleep.

A work by Alvin Zafra titled "Argument from Nowhere" (2000) has garnered some of the strongest audience reactions. One horrified young Japanese woman was overheard muttering '"sacrilegious." The seven-meter long set of panels appears to be a minimalist painting until one watches the video of Zafra creating the delicate shades of black and gray by vigorously scraping a human skull up and down the mounted sandpaper. Zafra said his motivation was "to paint a beautiful image of death."

Immortality and life in new forms, steeped in ethical debate, are deftly explored in works employing cutting-edge scientific and medical advances. Biotechnology -- genetic engineering, cloning, cell and tissue culture technology -- figures in important works by Patricia Piccinini and the bio-artists Stelarc, Eduardo Kac, and the husband-and-wife team Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr. Catts and Zurr head SymbioticA, the award-winning "artistic laboratory" at the University of Western Australia that has been called the "unofficial mother lode" of the bio-art movement. Their "semi-living" work "Victimless Leather - A Prototype of Stitch-less Jacket Grown in a Technoscientific 'Body'" (2004) courted controversy when it was shown at New York's MoMa in 2008. At the Mori show, this tissue culture work is placed within a life-sustaining portable mini-lab. Born from human and mouse cells cultured in a flask using biodegradable polymers, it is now growing into the shape of a tiny, flesh-colored kimono.

Brain science is one of the newest frontiers in medicine. Art is now testing those possibilities with mechanical interventions like the "Brain-wave-driven Wheelchair" (2009) developed by RIKEN BSI-Toyota. It's a wheelchair controlled by brainwaves, and one of the highlights of the exhibition.

Although the Medicine and Art show is embedded with ethical questions, it successfully reveals how art and medicine are inextricably connected, both of them deeply influencing the past, present and future of human health.

|

|

left: Magnus Wallin, "Exercise Parade"(2001); video installation with double back projection, 3D animated video

Courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin, Germany

right: Walter Schels, "Life Before Death - Elmira Sang Bastian" (14 January 2004/23 March 2004); photography

|

|

left: Damien Hirst, "Surgical Procedure (Maia)" (2007); oil on canvas

Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Courtesy of White Cube; © Damien Hirst, DACS, 2009

center: Leonardo da Vinci, "Two Studies of a Cranium" (1489); pen and ink, over traces of black chalk

Royal Collection, © 2009 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

right: Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty, "Dissection of a Pregnant Female Figure, Lateral View" (1764-65); oil on canvas

Courtesy of Wellcome Library

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lucy Birmingham

Based in Japan for almost 25 years, Lucy Birmingham has written for Newsweek, Bloomberg News, Architectural Digest, The Boston Globe, Artinfo.com, Artforum.com, and ARTnews, among other publications. As a photojournalist her work has appeared in The New York Times, Business Week, Forbes, Fortune, U.S. News and World Report, and A Day in the Life of Japan. She is also a scriptwriter and contributing editor at NHK, Japan's public broadcaster, and has published several books including Old Kyoto: A Guide to Traditional Shops, Restaurants, and Inns. |

|

|

|