|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Beauty of Japan in Oil Paint: The Nakagawa Kazumasa Art Museum

Alice Gordenker |

|

|

|

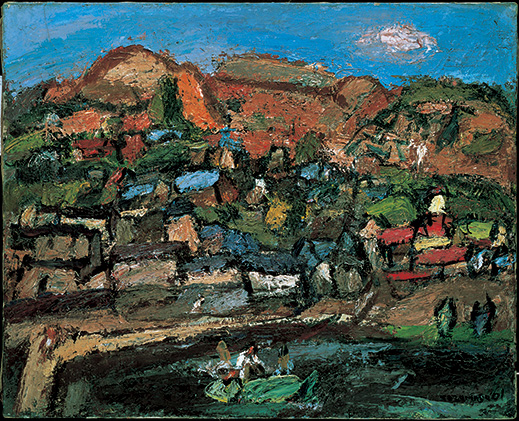

Kazumasa Nakagawa, View of Fukuura (1961), oil |

Sometimes a place becomes irrevocably linked with an artist who worked there. The French city of Arles was immortalized by Vincent van Gogh. The island of Tahiti immediately brings to mind Paul Gauguin. In like manner, the artist most closely associated with the small Japanese town of Manazuru is Kazumasa Nakagawa (1893-1991), a painter who made his base there for more than 40 years.

|

|

|

|

|

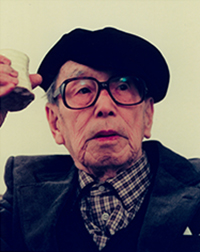

Kazumasa Nakagawa.

Photo by Koji Okabatake

|

Manazuru is located about 70 kilometers southwest of Tokyo on a small peninsula that juts into the Pacific Ocean. The land is steep and rocky, making it mostly unsuitable for agriculture, but the scenery is exceptional. On a chance visit, the Tokyo-born Nakagawa fell in love with the area, and in particular with a view of Fukuura harbor on the western side of the peninsula. He moved his atelier to Manazuru in 1949 in order to paint that and other local scenes, and ended up staying for the rest of his life. In 1989, the town returned the compliment by building a museum in his honor. Today, the Nakagawa Kazumasa Art Museum has the largest collection anywhere of Nakagawa's works, with about 80 on display at any one time.

The Nakagawa Kazumasa Art Museum in Manazuru, Kanagawa Prefecture |

Visiting the museum is an easy day-trip from Tokyo. It can also be done as a stop on the way to the better known tourist destinations of Hakone and Atami, although Manazuru offers plenty of its own amusements, including fishing, boat rides, and pleasant walking trails along the coast through a protected forest. Called the O-Hayashi (Great Wood) by locals, this verdant grove boasts deciduous trees that are hundreds of years old, a rarity in Japan where so many forests were ravaged for fuel during the Second World War.

Architecture aficionados will take special pleasure in the museum building, which won important prizes for its architect, Takahiko Yanagisawa, who also designed Tokyo Opera City, the New National Theater, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo. Of note are the exterior walls, which were made by pouring concrete into wooden molds; the lines of the planks and the grain of the wood are visible in the finished surface. The lobby is laid with a famous local stone called komatsuishi, a type of andesite that was also used in building Edo Castle and in the construction of many Japanese gardens.

Lighthouse of Manazuru (1968), oil on canvas |

|

Roses (1983), oil on canvas |

Although Nakagawa worked in many mediums, he is best known for his paintings in oil on canvas. European painting was introduced to Japan centuries earlier by missionaries and traders, but due to the country's policy of national isolation, very few Japanese had an opportunity to work in this style, or even view Western paintings, until after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Around this time, paintings done in Japan with European materials and techniques such as perspective and shading came to be called yoga (Western paintings), a term coined to distinguish them from traditionally-rendered works which were then referred to as Nihonga (Japanese paintings).

Nakagawa decided to become a painter after learning about the work of van Gogh and Paul Cézanne from the literary magazines that published his poetry. He attracted notice quickly and was soon part of a modernist movement that began in Japan around the 1910s, in which painters sought to express themselves as Japanese while working in the Western medium of oil paint. Perhaps the most famous artist in this group was Ryuzaburo Umehara (1888-1986), whose vibrant colors, dynamic brushstrokes, and liberated spirit greatly influenced young painters of the time. Nakagawa's earliest oil paintings are realistic and rather controlled, but he quickly found his own style in semi-abstract images rendered in bold colors and energetic brushwork.

|

|

Mt. Hakone-Komagatake (1975), oil on canvas |

Once Nakagawa found a theme he liked, he stuck with it. He painted the harbor at Fukuura again and again over a period of two decades, giving it up only when his view was despoiled by the construction of concrete buildings. His next subject was Mt. Komagatake in Hakone, which he painted more than 40 times in 16 years. When he got older and could no longer walk to paint from nature outdoors, he stayed in his atelier working on still lifes of roses or sunflowers. Such themes were popular with art buyers, and between sales of his paintings and commissions to illustrate books and magazines, Nakagawa made a good living with enough money left over for collecting.

In 1975 Nakagawa's career got a significant boost when he received the Japanese government's Order of Culture award. He could also count among his fans the Empress of Japan, who kept a Nakagawa painting in the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Although it was after his death, in 2010 both the Emperor and Empress came to Manazuru and made a stop at the Nakagawa Museum. His paintings continue to trade reasonably well when they come up for sale, and several major museums hold examples. In his mother's birthplace in Ishikawa Prefecture there is a second museum devoted to his work.

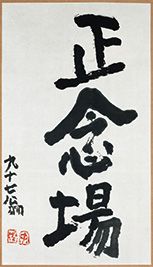

Even while working in the Western medium of oil paint, Nakagawa chose mostly Japanese subjects, and remained strongly focused on Asian culture. Throughout his life he practiced traditional arts including the tea ceremony, calligraphy, and poetry. He worked often in traditional Japanese mediums such as ink painting, ceramics, and iwa-enogu, which are richly colored paints made with pulverized minerals such as lapis lazuli and malachite. When Nakagawa collected he bought whatever inspired him, which was often Asian art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sakana kogiidete (1983), mineral pigment and Chinese ink on paper |

|

Calligraphy (1989), Chinese ink on paper |

Over the next year, beginning in April 2015, the Nakagawa Museum will present a series of four exhibitions showcasing the four seasons -- spring, summer, autumn and winter -- as seen in Nakagawa's art. If you visit the museum, be sure to stop afterwards at the municipal facility next door, where people play the uniquely Japanese croquet-golf hybrid called "park golf." Inside, Nakagawa's Manazuru atelier has been nicely re-created with furnishings and art supplies donated by his family after his death. The café that shares the space offers tasty buckwheat galettes at window tables overlooking the sea, allowing the visitor a glimpse of what it must have been about Manazuru that so charmed the artist Nakagawa.

All images courtesy of the Nakagawa Kazumasa Art Museum, Manazuru.

|

|

| |

Open 9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. (last entry at 4 p.m.)

Closed on the first and third Wednesdays of each month. Open on national holidays, but closed the following day. Also closed for New Year holidays (28-31 December).

1178-1 Manazuru, Manazuru-machi, Kanagawa Prefecture

Tel: 0465-68-1128 |

|

|

| |

Open 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (last entry at 4:30 p.m.)

Closed Mondays except on national holidays, when closed the following day, and for New Year holidays.

61-1 Asahi-machi, Hakusan, Ishikawa Prefecture

Tel: 076-275-7532 |

|

|

Alice Gordenker

Alice Gordenker is a writer and translator based in Tokyo, where she has lived for more than 16 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene she pens the "So, What the Heck Is That?" column for The Japan Times, which provides in-depth reports on everything from industrial safety to traditional talismans. She also writes about early Japanese photography. |

|

|

|