|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Beauty and the Eats: The Rosanjin Kitaoji Exhibition

Christopher Stephens |

|

Rosanjin Kitaoji, Momoyama-style Covered Lacquer Bowls with Grass Design (1944), National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Collection |

In 2013, washoku (Japanese cuisine) was added to the register of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritages -- a list that currently includes 314 elements, among them shrimp fishing on horseback, a custom practiced in Oostduinkerke, Belgium, and a whistled form of Castilian Spanish exclusive to La Gomera in the Canary Islands. Based on a reverence for nature and a fondness for fresh seasonal materials, washoku refers to a complex system of preparing, consuming, and presenting food. It is surprising to learn, however, that many aspects of what seems to be an age-old tradition date to the 20th century and the efforts of one man.

Kitaoji Rosanjin: A Revolutionary in the Art of Japanese Cuisine, an exhibition continuing through August 16 at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, introduces the many talents of legendary epicurean and aesthete Rosanjin Kitaoji (1883-1959), an accomplished calligrapher, seal engraver, ceramicist, and cook.

Kitaoji’s life did not begin well. His father, the head priest at Kamigamo Shrine in Kyoto, committed suicide a few months before he was born, and his mother abandoned him soon after. Kitaoji spent his first few years being shuffled from one relative to another until, at the age of six, he was apprenticed to a wood carver, and then at ten, to an herbalist. An exhibition he saw at 12 inspired him to pursue calligraphy as a career. In his twenties, Kitaoji found work at a government printing bureau in Korea (then under Japanese rule) and traveled to China while developing his calligraphic and carving skills further. After returning to Japan in 1913, he stayed with a series of cultured friends in Shiga, Kyoto, and Kanazawa who sparked his interest in antiques, cooking, and pottery.

|

|

Rosanjin Kitaoji, Rectangular Oribe Dish (1949), National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Collection |

Kitaoji took all that he had learned and in 1919 opened the Taigado antique shop in Tokyo with Takeshiro Nakamura, a recent acquaintance. Rather than simply selling curios, he came up with the idea of using the merchandise to serve food, and opened the Bishoku Club (Gourmet Club) upstairs from the shop. This caused a sensation with well-heeled diners and led to the launch of a full-scale, members-only restaurant called Hoshigaoka Saryo in the Nagata district of Tokyo in 1925, with Nakamura as proprietor and Kitaoji as artistic adviser-cum-head chef. Part of the restaurant’s appeal lay in Kitaoji’s unstinting hospitality. He went to great lengths to procure regional delicacies from all over the country, serving them to guests like the novelist Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Charlie Chaplin at special breakfast parties and garden fetes.

Kitaoji also began to make his name as a ceramic artist in a series of shows at Hoshigaoka Saryo, and in the late ’20s, he opened a pottery studio in Kita-Kamakura to create the ideal tableware for the restaurant. As he saw it, tableware was a “kimono for food,” with the shape, color, and material of each vessel complementing the dish and triggering a dialogue between the two. Among his innovations are the now ubiquitous chopping-board-shaped plate and extremely large bowls (some measuring up to 20 centimeters in height and 40 centimeters in width). To decorate his creations, Kitaoji used stunning seasonal motifs like red and white camellias on a beige ground, or streams of cherry blossoms gradually morphing into crimson maple leaves. He also made sets of small leaf-shaped plates, round plates ornamented with small crabs, birds, and string-like strands of color, and covered lacquer bowls in matte black with vermilion turnip designs.

|

|

Rosanjin Kitaoji, Dishes with Spool of Cotton Thread Design (c. 1945), Adachi Museum of Art |

By the summer of 1936, the staff at Hoshigaoka Saryo had swelled to 90. Ever committed to outstanding service and quality, Kitaoji had arranged for live ayu (sunfish) to be transported from Kyoto to Tokyo, and prepared 8,000 pieces of tableware for the opening of a new branch in Osaka. It was just at this point that he received a letter of dismissal from Nakamura, who had apparently grown tired of Kitaoji’s domineering manner and carefree spending habits. Kitaoji responded with a legal suit against his former partner that dragged on for a decade. This was one of many severed relationships in Kitaoji’s life (he was married and divorced five times), and probably contributed to his enduring reputation as an arrogant and difficult man.

The truth, especially after World War II, was much different. As a cook, Kitaoji had always savored every morsel of food, carefully making use of things like fish scales and vegetable peels that would normally be discarded, but in the late ’40s, he was so impoverished that he was unable to pay the electric bill at his pottery studio and forced to rely on friends to provide him with the cooking ingredients he craved. He repaid them with his works, which he continued to show in exhibitions and sell at his own shop in Ginza (the hand-painted sign outside included the English legend “Beautiful, Useful, Cultural - Specialty Shop of Rosanjin Greatest Artist”). Though his popularity had waned since his heyday in the ’30s, Rosanjin now began to attract a foreign following. With the help of John D. Rockefeller III, the chairman of the America-Japan Society, Kitaoji staged a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1954, and on the way back to Japan stopped off in France, where he met Picasso and Chagall. The following year Kitaoji was offered the status of Important Intangible Cultural Asset in Oribe-yaki ceramics (notable for their green copper glaze and bold abstract designs), but in typical style, he refused. He died of cirrhosis in 1959 at the age of 76.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mikio Hasui, Kyoto Kitcho-17 (2015) |

|

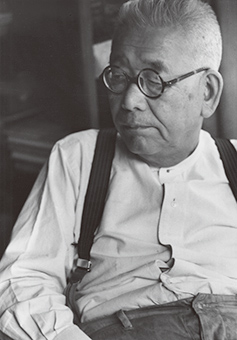

Rosanjin Kitaoji (photo by Ken Domon) |

|

All images provided by the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. |

The Kyoto exhibition consists of approximately 120 works, as well as documents related to the artist and a handful of impressionistic photographs and videos taken by the contemporary artists Yoshihiko Ueda, Yasushi Hirokawa, and Miko Hasui at three traditional Japanese restaurants. A video installation recreating the counter at Kyubey, a sushi restaurant in Ginza, is also a nice touch, giving the viewer a better idea of how this attractive tableware might look when actually used to display food.

In later years, Kitaoji recalled how at the age of three he had discovered a clutch of bright red azaleas on a hill behind Kamigamo Shrine. The sight filled him with such a powerful sensation that he immediately knew he was born to spend his life in pursuit of beauty. By all accounts, this is exactly what he did, but fortunately for us he also made the world a much more beautiful place while he was here.

|