|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture and design exhibitions and events at art museums, galleries and alternative spaces around Japan. The contributors are non-Japanese art critics living in Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Uncovering the "Living Skills" of Kanazawa Machiya: An Exhibition of Craftsman Techniques at LIXIL Gallery

James Lambiasi |

|

Sliding wooden doors of the former Wakunami family house, a Kanazawa Designated Cultural Property. This machiya is thought to have been built during the late Edo period, but was restored in 2003 to its Meiji-era state. The first floor is currently on display at the Higashi Chaya Kyukeikan in Kanazawa. Photo: Yosuke Owase |

As one of the thriving urban centers in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867), the castle town of Kanazawa saw prolific growth of the urban townhouse structures called machiya. Kanazawa was spared the fires and disasters that have eradicated these structures from most Japanese cities, so thankfully the machiya built there by generations of craftsmen still exist today. They were places where work and life coexisted, serving functions ranging from common retail shops to delicately crafted geisha houses.

This is the subject of the current exhibition at Tokyo's LIXIL Gallery, Machiya: Kanazawa's Traditional Townhouses -- The Living Skills of Townhouse Craftsmen, which uncovers and explains many of the individual crafts that come together in a single machiya. The title very appropriately refers to the skills of the craftsmen as "living skills," because without their continued attention and maintenance, the diligently constructed machiya would eventually fall into disrepair. One could say that the building craft is a living art, and the machiya beautifully reveal to us the techniques the artisans needed to hand down from one generation to the next.

To explain the crafts involved, the exhibition highlights seven of the main "living skills" that combine to create a machiya: carpentry, masonry, roofing, plastering, tatami, fittings, and mounting. Each is explained in detail through a display of the tools and materials used. Photographs, explanatory models, site reports of actual repairs, and, most importantly, detailed interviews with the craftsmen themselves help to piece together an understanding of the amazing complexity behind each machiya.

The explanatory text of the exhibits is basically only in Japanese; despite this, however, the visual quality of the displays allows one to comprehend the seven crafts even without a reading knowledge of Japanese. As I read through the explanations, I appreciated how the content focused on the "living skills" aspect of each craft. I thought I would share some of these thoughts in this article to give you an overview of these seven "living skills," hoping it will serve as a bit of a guide through each exhibit.

1. Carpentry

|

Wood joinery models created by craftsman Shotaro Yasuda reveal the astonishing precision used to make joints that can lock in place. |

Tools provided by Shotaro Yasuda. |

The wide variety of carpentry tools on show demonstrates the complexity of creating the precise joinery making up the structure of the machiya, conveying this through a hands-on exhibit of models of different joinery methods. Each cut in the wood has a different characteristic and therefore requires a specific tool, which is evident in the diversity of tools in the display. Before earning the privilege of wielding them, apprentices new to the trade are first relegated to sharpening the tools and sweeping the site.

A transparent plastic model by Shotaro Yasuda shows the complex intersection of wood members at several different angles. |

2. Masonry

|

Some of the masonry tools of craftsman Akira Deguchi. The hammer in the middle of the display has a sashi-bajiru detachable tip. |

Stone is cut, shaped, textured, and polished, each treatment requiring specific tools and methods. Of the tools on display I was particularly impressed with the sashi-bajiru hammer, which has a detachable tip that can be quickly replaced. Compared to the hard stone, the sharply tipped iron is relatively soft and goes dull after some use. Because the tip is detachable, a replacement tip can be heated by fire and re-sharpened to be ready for a quick change.

3. Roofing

Roofing tools of craftsman Kazuaki Osada. |

|

|

|

|

|

Zentokuji temple in Kanazawa; the roof is under construction by Kazuaki Osada.

|

The "living skills" of the roofing craftsmen are evident throughout the process of replacing the kawara tiles. In order to make a suitable replacement tile, for example, the type of soil used at the production site is first investigated. The gentle curve of a kawara roof actually has great physical logic; it is a natural parabola that works in harmony with gravity, pulling the pieces downward and strengthening their interlocked position. Despite their interchangeable appearance, every one of the tiles is made of natural material and therefore has its own individual characteristics. Fitting them together is therefore an extremely involved process, and it is necessary to test-fit the tiles like a jigsaw puzzle.

4. Plastering

Plastering tools provided by craftsman Kou Nakamura.

|

A model provided by craftsman Hideki Fujita, showing the intricate layers of a typical plastered wall. The fibers hanging from beneath the beam are an example of hige-maki, an Edo-period Kanazawa technique that formed a strong bond to the frame and resisted cracking even in earthquakes. |

Not only were the techniques of the Edo-era plaster craftsman complex, but their relationship to the machiya over time was also conceived differently, as part of the truly "living" craft of konaka-shiage. In those days a properly built plaster wall was not constructed in one instant, but over decades. Once the base wall was constructed it was allowed to dry and settle for several years. To commemorate important social occasions or family milestones, the artisan was commissioned at a later time to add an additional plaster layer, so over the years a supremely smooth and resilient surface resulted.

5. Tatami

|

An "elbow cap" allows craftsman Katsunori Tachino to concentrate pressure onto the tatami mat. |

The tools of the tatami mat craftsman poignantly convey what a living skill this truly is, in that the relationship of the body and the tatami construction process is so intertwined. An "elbow cap" allows the craftsman to strategically apply pressure to the tatami as stitching holds the pressed fibers together. A protective cloth that fits perfectly in the palm of the hand lets him push a needle through layers of matted fibers. Equally impressive is the combination of natural tree and grass fibers; a properly made tatami mat is said to last over a century.

Tatami mat sample showing an outer layer of palm tree fiber.

|

6. Fittings

|

Intricate detail of wood fittings and the tools required; display provided by craftsman Morio Nishida. |

By all appearances a Japanese shoji screen conveys calm simplicity; the process of crafting one, however, is full of complexity. A vast array of tools is necessary to produce the many types of chiseled notches in the wood, as is evident from the display here. One particularly interesting detail is a shoji by craftsman Morio Nishida with a subtle curve holding a small stained-glass fitting. The curved element in the shoji appears simple enough, but the stresses it produces within the intertwined elements cause great technical difficulties to resolve. This delicate curve, therefore, is actually a way to showcase the technical prowess of the artisan.

The delicate curve incorporated into a shoji screen by Morio Nishida. |

7. Mounting

|

|

|

|

|

|

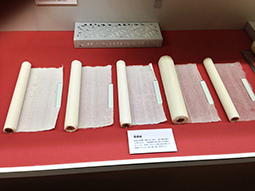

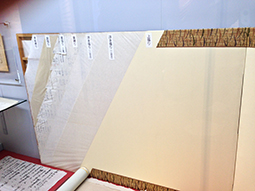

Several types of paper used in a typical Japanese screen, provided by craftsman Akira Nagashima. |

|

A model display of the several layers used in a Japanese screen. |

As with all of the skills featured in this exhibition, the intricacy of paper mounting for Japanese screens and fusuma sliding doors belies the simplicity of their appearance. In addition, many of the craftsmen were artists in their own right, as the paintings they applied to the screens attest. An interesting aspect of the "living skills" of this art is the quality of the glue used. A simple mixture of flour and water, it was intended to be impermanent and allow for future repairs and paper replacement; ironically, it is the impermanence of the material that ensures its longevity.

Through these seven exhibits of carpentry, masonry, roofing, plastering, tatami, fittings, and mounting, the exhibition offers a great educational opportunity to learn more about Japanese craft. Indeed, a visit to LIXIL Gallery to encounter these "living skills" first-hand may inspire you to someday visit the machiya townhouses of Kanazawa as well.

All photos by James Lambiasi except where otherwise indicated. All images are shown by permission of LIXIL Gallery.

|

|