|

|

|

| Shoeita Kikuchi, Still Life (1982) |

|

Shoeita Kikuchi, Farewell, Zenmai Picker (2001) |

The broad sweep of the southern slopes of Yatsugatake, an ancient volcanic massif on the Nagano-Yamanashi border in central Honshu, offers vistas of wide-open space that most visitors would not associate with Japan. The pristine alpine environment and relative proximity to Tokyo (only two hours by express) have long made this area a popular retreat from the capital for urban artists, but it also boasts many homegrown talents. One such favorite son, born in the highland village of Hara, was the sculptor and painter Takashi Shimizu (1897-1981). When Shimizu donated his works to his hometown in 1978, it spurred the village to construct the Yatsugatake Museum of Art, which houses over 100 of his sculptures and paintings.

Designed by the modernist architect Togo Murano (1891-1984), the museum opened in 1980 in a larch forest high up on the slopes of Yatsugatake. With its rows of small domes connected along perpendicular axes, it is a curious structure that brings to mind the space station in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Inside, however, the ambience is spacious and inviting. White bunting suspended from the domed ceilings softens the mountain light pouring in through the windows, creating an intimate, even exotic mood (think Arabian Nights!) that encourages leisurely viewing of the art on display.

|

|

|

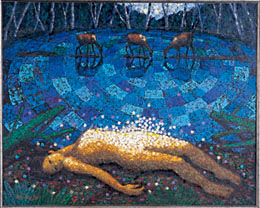

| Shoeita Kikuchi, Such a Sweet Embrace (2006) |

|

Shoeita Kikuchi, Weaving on a Heavenly Loom (2004) |

The museum's expansive galleries enable it to hold special exhibitions of considerable scale. Its most recent offering was particularly ambitious, in that it provided the first joint retrospective of two remarkable artists with a special bond. Shoeita and Hoshime Kikuchi were together for 50 years but worked in completely different media. They met in art school, married upon graduation in 1952, and would serve as one another's muse until Hoshime's death in 2001. A painter of impressionistic still lifes, Shoeita took a day job in a Tokyo newspaper art department, while Hoshime launched a successful career as a designer of children's hats. By 1980, however, they had tired of city living and relocated to a house on Yatsugatake -- coincidentally, the same year that the Yatsugatake Museum opened.

The new environment had a dramatic impact on both of them. Shoeita, who had continued to devote himself to still-life painting during all those years in the city, began to incorporate motifs from the surrounding fields and forests: not only flora, but fauna such as pheasants, deer, wild boar, and the

kamoshika or Japanese serow, an indigenous beast that looks like a cross between a mountain goat and an antelope. His work became more fanciful, even hallucinatory, with humans and animals coexisting in close proximity amid a lush jungle of alpine trees and plants. The effect is something like the tropical visions of Henri Rousseau or Isson Tanaka transplanted to an alpine setting.

|

|

|

| Hoshime Kikuchi, Kimono fabric dyed with longstock holly; weft: zenmai; warp: silk |

|

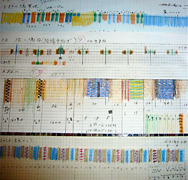

Sketch of weaving designs by Hoshime Kikuchi |

Meanwhile, Hoshime had found inspiration in the upland meadows to pursue a new vocation at age 56 -- as a weaver. On the slopes above their home grew a profusion of

zenmai, the Japanese royal fern, which has a soft cottony down on its underside. Venturing out daily during the summer season, she gathered basketsful of zenmai, removed the down, and spun it into yarn, which she colored with natural dyes she made from other local plants. Weaving this

zenmai wata (literally "fern cotton") together with silk or cotton thread, she began to produce cloth of subdued yet stunning beauty, in patterns worthy of an abstract painter.

Hoshime rapidly earned acclaim in Japanese folkcraft circles for her weaving, but this late-blooming career was cut short when she died of a sudden illness at age 70. The loss was devastating to her husband, to whom she had been both partner and inspiration for half a century. Once again, Shoeita's art underwent a transformation. He began incorporating his wife's figure into his work, adding new motifs such as concentric circles of blue mosaic, perhaps representing the firmament to which she had returned. Always present, too, are the totemic kamoshika, her guardian spirits as she quietly gathers zenmai in the meadow.

|

|

|

| Installation view of kimono and shawl fabrics dyed and woven by Hoshime Kikuchi, Yatsugatake Museum |

|

Sculptures by Takashi Shimizu in the permanent collection wing of the Yatsugatake Museum |

For the Kikuchi retrospective, the museum's intersecting series of domed galleries provided ample room for both artists. Rather than try to intermingle the works of two people who, despite their intimacy, were clearly independent souls, the curator wisely let each artist's oeuvre create its own ambience. Thus visitors entered a broad, high-ceilinged hall lined with Shoeita's paintings, which ranged from his early still lifes to the phantasmagoric depictions of Hoshime, which he continued to paint until his own death in 2010 at age 80. Meanwhile, a cozier gallery under a single dome offered a 360-degree panorama of Hoshime's wall hangings as well as displays of her dyed yarn, tools, and preliminary sketches for the weaving patterns she invented.

The Yatsugatake show was an inspired and much-deserved tribute to the Kikuchis, but unfortunately it ended too soon for many visitors outside of the area to appreciate it. One hopes that the same exhibition will eventually find its way to venues in Tokyo and elsewhere, for both artists certainly merit wider recognition.

Currently on view at the Yatsugatake Museum until March 31 are sculptures and paintings by Takashi Shimizu, commemorating the 30th anniversary of his death, and a special exhibition of the paintings of contemporary artist Masashi Soma. Also on permanent display is a fine collection of locally excavated Jomon pottery and stone implements, testifying to the extent of the Neolithic culture that flourished in the area 4,500 years ago.

|

|

|

| Aerial view of the Yatsugatake Museum of Art, designed by Togo Murano in 1979 |

|

Shoeita and Hoshime Kikuchi in a meadow near their Yatsugatake home

All images courtesy of the Yatsugatake Museum of Art |