|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bicultural Book Design: Tsuguharu Foujita at the Hibiya Library & Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

|

|

| Flyer for the Tsuguharu Foujita exhibition at the Hibiya Library & Museum, featuring a photograph of the artist taken around 1928 by André Kertész. (Ullstein bild/Uniphoto Press) |

|

The façade of the triangular Hibiya Library & Museum, flanked by the foliage of Hibiya Park, with downtown highrises in the background. Photo by Alan Gleason |

Tsuguharu (a.k.a. Leonard) Foujita (1886-1968) is revered in Japan as the first local boy to make good as an artist overseas, and in France no less. He enjoyed remarkable success during his first long sojourn in Paris from 1913 until 1931, achieving both fame and financial security unrivaled among the loosely affiliated group of expatriate artists known as the School of Paris. He went through a number of styles, including an early stint as a cubist, but is best remembered for his portraits of women and cats -- the former in particular for their luminescent white skin, which he painted with a secret mixture called "le grand fond blanc."

After a brief period in South America, Foujita returned to Japan in 1933 as something of a celebrity, but during the war years he was recruited by the military to produce heroic paintings of Japanese soldiers in battle, which he did with great gusto. This devotion to the patriotic cause made the artist a target of criticism after Japan's surrender, and in 1950 he moved back to his beloved France, where he acquired French citizenship, converted to Catholicism, and never returned to his homeland again. (See this review in the August 2006 issue of artscape for more on Foujita's art.)

In France, then in Japan, then in France again in his final years, Foujita was always in high demand as an illustrator and designer of books and magazines. Though this part of his oeuvre may not be as acclaimed as his paintings, the exhibition now on view at the Hibiya Library & Museum in downtown Tokyo demonstrates just how nimbly Foujita shuttled between Japanese and French motifs in his work for publishers in both countries. Elements of his painting style, particularly his fluid line work, worked well in an illustrative context. Delicate yet strong, Foujita's lines remind this writer above all of Nihonga, but as Matthew Larking notes in the "Focus" article cited above, they may have been equally inspired by Picasso, Diego Rivera, and ancient Greek and Egyptian art.

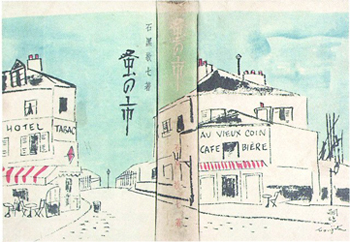

Foujita was particularly adept at accommodating his clients' demands for exotica, illustrating French publications with Noh masks and geisha, then offering up quaint Parisian street scenes to grace the covers of Japanese periodicals (a highlight of this show is the series of covers he did in 1935 for the fashion magazine Fujin no tomo). Examples of this bicultural fluency can be seen in the works shown here -- one the wraparound cover illustration for a Japanese book by judo practitioner Keishichi Ishiguro about his time in Paris, the other the cover for a collection of Japanese folktales published in France.

|

|

|

| The cover of Nomi no ichi (Flea Market) by Keishichi Ishiguro, designed by Foujita in 1935. Image © ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2013 E0474 |

|

The cover of Legendes Japonaises, compiled and illustrated "par Foujita" in 1923. Image © ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2013 E0474 |

Also noteworthy is a set of a half-dozen black-and-white prints by renowned photojournalist Ken Domon (1909-90) that show Foujita painting in his studio in Tokyo. This was an artist who was notorious for his fear of imitators, and these images shot by his friend Domon may be the only visual record Foujita ever permitted of himself at work.

The Hibiya Library & Museum is an eminently appropriate venue for this show, and not only because the works on display are mostly books and magazines. First opened in 1908 as the Tokyo Municipal Hibiya Library, the venerable institution came under the jurisdiction of Chiyoda Ward in 2009 and reopened as a combination library and museum in 2011 after extensive remodeling. Chiyoda is where Foujita lived and worked from 1937 to 1944. With its link to local history as well as to art and publishing, the exhibition thus dovetails on several levels with the facility's new identity. The current building, which dates to 1957, boasts a quintessentially eccentric fifties-modern design -- it forms a perfect equilateral triangle. In addition to the large gallery reserved for special exhibitions like the Foujita, the facility has an equally spacious permanent exhibit of Edo- and Tokyo-related historical paraphernalia.

A fringe benefit of checking out the Foujita show is that the library/museum sits in Hibiya Park, a compact but attractive expanse of greenery smack in the center of Tokyo, with the Imperial Palace on one side and a phalanx of skyscrapers looming on the other. Opened in 1903 on the site of a former military drilling ground, Hibiya is actually Japan's first western-style public park, and it continues to offer a pleasant respite from the hustle and bustle of the megalopolis that surrounds it.

|

Installation view of the Foujita exhibition, with book and magazine covers displayed in flat cases and along the walls.

All images courtesy of the Hibiya Library & Museum unless otherwise indicated. |

|

|

|

Tsuguharu Foujita: Book Design in Japan (in Japanese only)

4 April - 3 June 2013

Hibiya Library & Museum |

|

1-4 Hibiya-Koen, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3502-3340

Museum hours: 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. (to 7 p.m. Saturdays and 5 p.m. Sundays and holidays); closed on the third Monday of the month and during the New Year holiday

Transportation: 3 minutes' walk from Uchisaiwaicho Station on the Toei Mita Line or Kasumigaseki Station on the Metro Chiyoda and Marunouchi Lines |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|