|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

That Was the Year That Was: Japanese Photography in 1968

Alan Gleason |

|

|

| Shigeo Gocho, from the series Days, 1967-70, gelatin silver print, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. |

On show until July 15 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in Ebisu, 1968 -- Japanese Photography does not actually restrict itself to one year, watershed though 1968 undeniably was. The time frame indicated by the subtitle, "Photographs that stirred up debate, 1966-1974," is a sensible one for examining the precursors as well as the aftermath of the explosive events of that pivotal year, both in Japanese photography and in the world at large.

|

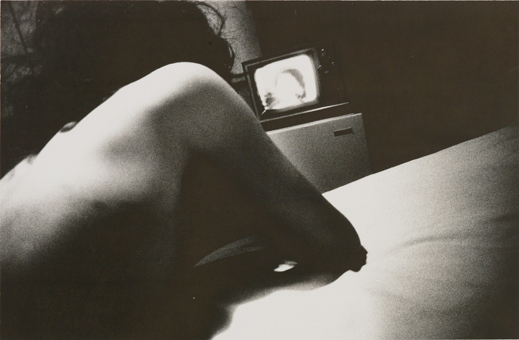

| Daido Moriyama, untitled, from the magazine Provoke No. 2, 1969, gelatin silver print, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. |

What happened in Japan in 1968? Really, what didn't happen? Japan, no less than the United States, was already embroiled in the Vietnam War, serving as a primary launching point for American military operations in that conflict. College students opposed Japan's role in the war and the security agreement with the U.S. that dictated it, but also harbored grander aspirations. 1968 was the year when campuses throughout the nation were occupied by students with radical social change in mind, inspired to no small degree by the Cultural Revolution spearheaded by the youthful Red Guard in neighboring China. Others joined protesting farmers in the struggle against construction of the Narita International Airport at Sanrizuka. Even less overtly political students and artists were stimulated by the ferment in the air to challenge authority on every level.

|

| Sanrizuka Shashin no Kai, from the series Sanrizuka, 1971, gelatin silver print, private collection. |

It was a heady time for photographers, too. Mavericks like Shomei Tomatsu zeroed in on controversial topics like the U.S. occupation of Okinawa or the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and such acolytes as Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira challenged the stylistic status quo with their are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus) manifesto, producing dark, unsettling monochrome work that perfectly encapsulated the mood of the times. Photographers launched magazines like Provoke: Provocative Materials for Thought and formed collectives like the All Japan Students Photo Association. Some traveled to Hokkaido to document life on the still-harsh northern frontier, chronicled the environmental damage caused by Japan's postwar industrial juggernaut, or, like Kazuo Kitai and Hitomi Watanabe, joined students behind the barricades and captured campus occupations from the inside. (It is a telling indicator of the sexual politics of the era that Watanabe is the only female photographer among the 36 artists represented here; adding to the irony, she is erroneously represented as male in the otherwise excellent English translation of the exhibition catalog.)

|

| Seiichi Takebayashi, Horonai Station, Hokkaido, c.1871-80, albumen print, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. |

As in China, Europe, and North America, however, the tension could not be sustained indefinitely. After riot police broke through the barricades and hauled striking students off to jail, the moment of youthful insurrection passed, to be followed by the quietistic, hedonistic seventies. Emblematic of this shift was Nobuyoshi Araki's self-published 1971 volume of photos from his honeymoon, Sentimental Journey; Araki went on to stardom as a purveyor of sexually provocative imagery. Tomatsu, meanwhile, earned accolades for The Pencil of the Sun, his 1975 collection of photos taken in Okinawa before and after its 1972 reversion to Japanese possession. Though the work acknowledges the upheavals that wracked the islands during that period, most of it focuses on Okinawa's natural beauty and the daily lives of its inhabitants.

For anyone who actually remembers the sixties, of course, the sturm und drang depicted in these photos will seem like old news. Indeed, the images I found the most novel and fascinating were those in a section at the very beginning of the show, from the seminal exhibition A Century of [Japanese] Photography organized by Tomatsu, Nakahira, and others in 1968. Gathered here are striking shots, by the nation's earliest photographers, of mid-19th-century Japan: out-of-work samurai and the ruins of Edo Castle after the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate, or indigenous Ainu and hardscrabble frontier settlements in Hokkaido.

Clocking in at some 300 photos, all in relentless black and white, 1968 is almost too much to digest in one visit. But there is no denying its value as a thorough documentation of the most tumultuous epoch in postwar Japanese history, one whose drama has yet to be duplicated either in style or content. The same can be said for the photography it spawned.

|

|

A lecture at the 1968 -- Japanese Photography exhibition.

All images courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. |

|

|

|

1968 -- Japanese Photography

Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

11 May - 15 July 2013

|

|

Yebisu Garden Place, 1-13-3 Mita, Meguro-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3280-0099

Open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (to 8 p.m. on Thursdays and Fridays); admission until 30 minutes before closing

Closed Mondays (or the next day when Monday is a national holiday)

Transportation: 7 minutes via the Sky Walk from JR Ebisu Station, east exit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 28 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|