|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Wild Man of Picture Books: Koji Suzuki at the Chihiro Art Museum

Alan Gleason |

|

|

Koji Suzuki's "live paintings" in the main gallery of the Chihiro Art Museum |

Somewhere I read a quote from a prominent children's-book illustrator who said he preferred drawing for young readers more than for adults because he could draw what he pleased, no matter how crazy.

Firmly at the "crazy" end of the picture-book spectrum is Koji Suzuki, an artist whose boundless imagination and protean palette have kept kids of all ages in stitches for many decades. Arguably he is Japan's answer to Maurice Sendak, for there seems no end to the wild things that spring fully formed from Suzuki's fevered brain. Until May 24, the Chihiro Art Museum in western Tokyo is giving over the better part of its ample gallery space to a thrilling and hilarious romp through Suzuki's wacky world.

Japan is a picture-book illustrator's paradise. Though I have no statistics to back me up, I'd wager that it rivals manga as a profitable publishing niche. After all, preschool toddlers seem unlikely to switch to ebooks and smartphones en masse. Manual dexterity issues aside, they like big colorful pictures, as well as having someone turn the pages and read to them. Hopefully this is one market for which works printed on paper will not become obsolete anytime soon.

|

|

|

|

|

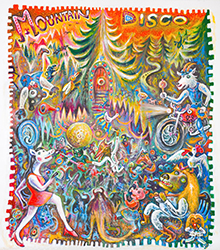

Mountain Disco (2013), a painting by Suzuki based on his 1989 picture book of the same title

|

Add to this a cultural tradition that gives the picture book its due as a legitimate artistic medium, and you have fertile ground in Japan for some very talented artists tilling the kiddie-lit field. Indeed, the existence of the Chihiro Art Museum -- an entire facility dedicated to the work of one particularly beloved children's-book illustrator, Chihiro Iwasaki -- testifies to the genre's popularity.

Though Suzuki's drawing style is the polar opposite of Iwasaki's, which tends toward limpid watercolors of doe-eyed tots, he shares with her an instinctive knack for viewing the world through a child's eyes. There is nothing patronizing about his stance toward his young audience; this is one guy who not only taps into his "inner child" but fully revels in it. His work is full of creepy-crawlies, grinning skeletons, disco-dancing forest creatures, animated vegetables, and livestock running amok (see his 1995 masterpiece Ushibasu ["Cow Bus"] for the ultimate wild-ride adventure). Yet there is no dark side to his work -- no violent or erotic overtones, no ominous hints at the presence of forces of evil -- and this makes him the ideal guide for prepubescent children accessing an unfettered but still relatively innocent subconscious.

|

|

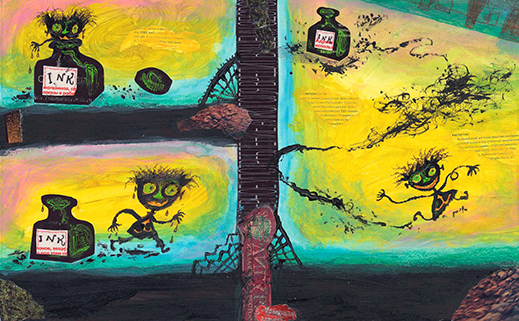

Illustration from Suzuki's picture book Blackinder, 2008 |

Suzuki, who was born in Shizuoka in 1948, began drawing at a tender age. Having decided early on that this was what he wanted to do for the rest of his life, he was apparently a bit of a rebel in school. As soon as he could he moved to Tokyo and snuck into classes at some well-known art schools, but never enrolled. Along the way he picked up the nickname Kojizuking (he has puckishly named the current exhibition St. Kojizuking's Temptation) and demonstrated a maverick streak by holding his first solo show on the streets of Kabukicho, Tokyo's sleaziest bar district. It was the sixties, and judging by photos of him from that period, as well as his artistic output, Suzuki appears to have fully absorbed the spirit (and perhaps a few of the spirits) of the psychedelic era.

|

|

|

|

|

Illustration by Suzuki from Yuki-musume (The Snow Maiden), 1971 |

Fortuitously his talents attracted the eyes of some influential art directors and he found employment as a magazine illustrator. He made his picture-book debut in 1971 with illustrations for a Japanese adaptation of the Russian tale The Snow Maiden, and won the first of many prizes in 1987 with his original work Enso's First Trip Alone, still a perennial favorite. Early efforts like The Snow Maiden show a relatively orthodox approach to illustration. While they have Suzuki's trademark bold lines and coloring, the faces of the characters are standard-issue "cute" -- an adjective not often associated with his later work.

Suzuki's illustrations are a remarkable balance of order and chaos. The chaotic aspect is deceptive; though he takes a wall-to-wall, fill-every-nook approach to the canvas, every detail is meticulously, perfectly placed. You can spend a long time looking at just one of the pages in his books. For that reason, the Chihiro show may take several hours to wade through, thanks to the sheer volume of goodies for the eye to feast on. It is a generous presentation, with original art from his many picture books supplemented by whimsical displays that range from sprawling tableaux of painted objects -- broken musical instruments, toy trains, discarded boxes -- to a series of portrait paintings on toilet seats.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suzuki's atelier as re-created at the Chihiro Art Museum Azumino, with a "live painting" based on Salubilusa; it is now on display at the museum's Tokyo facility. |

|

Suzuki at work on the painting. |

The spacious, high-ceilinged main gallery is hung with tapestry-like "live paintings," huge works Suzuki began producing ad-lib on city streets in the 1990s. In one corner is a reproduction of his atelier; the finished painting that hangs there is featured in a video that traces its progress, interspersed with footage of Suzuki taking a break by prancing around the studio with his electric guitar.

The painting happens to be based on one of Suzuki's more "serious" children's books, an antiwar tour-de-force titled Salubilusa that nails the absurdity of armed conflict in its depiction of a war between two mythical countries who speak languages that are the mirror image of one another. Despite the heavy theme, Suzuki makes his point through satire that is just as funny as it is thought-provoking.

|

Illustration from Suzuki's picture book Salubilusa (1991) |

Further evidence of Suzuki's serious side is a corner devoted to his Chernobyl-related work. Inspired by Seiichi Motohashi's photographs of people in the fallout-tainted areas of Eastern Europe, Suzuki has created a series of "No Nukes" collages that make clear his stand on the issue.

With so much to stimulate the eye, mind, and funnybone, this is a show I can wholeheartedly recommend to anyone -- but if you have a young child, it's a must! Be forewarned, however: Suzuki's gonzo worldview may permanently warp your little one's take on reality, if not your own.

The "hot" and "cool" sides of Holy Heater-Cooler, a peek-a-boo installation for kids

on the museum's garden veranda. Photos by Alan Gleason

All images © Chihiro Art Museum |

|

|

| |

4-7-2 Shimo-Shakujii, Nerima-ku, Tokyo

Phone: 03-3995-0612

Hours: Tuesday-Sunday, 10-5

Closed Mondays except on holidays (closed the following Tuesday); also closed on New Year holidays and between exhibitions

Transportation: 7-minute walk from Kamiigusa Station on the Seibu Shinjuku Line |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|