|

|

Here and There introduces art, artists, galleries and museums around Japan that non-Japanese readers and first-time visitors may find of particular interest. The writer claims no art expertise, just a subjective viewpoint acquired over many years' residence in Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lonely Crowds: Kiyokazu Yonetani at the Mitaka City Gallery

Alan Gleason |

|

|

Snowy Day (1984), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 205 x 580 cm; collection of Narukawa Art Museum. |

Kiyokazu Yonetani employs the traditional materials of Nihonga-style painting to decidedly untraditional ends. He works mostly with mineral pigments on kumohada mashi ("cloud-surface hemp paper"), a type of washi made of hemp and mulberry in his home prefecture of Fukui. But that is pretty much the extent of his allegiance to Nihonga conventions. Working on large canvases, many around two meters square, he slathers the pigment on thickly, often in loud primary colors. Yet the dominant tone of his early work is black -- the black of a Tokyo commuter's overcoat.

|

Station (1974), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 187 x 230 cm. |

Though his stark portraits of anonymous crowds in train stations are what first grab the eye, the current Yonetani retrospective at the Mitaka City Gallery of Art amply demonstrates how he has evolved through a number of stages to a place that is literally and figuratively far removed from that early subject matter. These stages are loosely correlated to the show's title, Shibuya, Shinjuku, Mitaka -- the three Tokyo neighborhoods that provide the settings of so much of his work.

|

Shinjuku Platform 5 (1976), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 174 x 205 cm. |

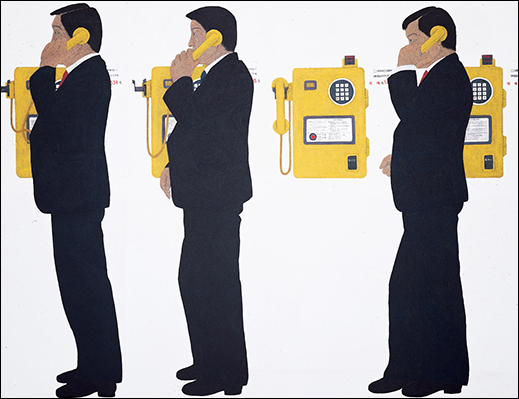

Born in 1947 near the Sea of Japan coast, Yonetani came to Tokyo in 1967 to study at Tama Art University with his hero, the prominent Nihonga artist Misao Yokoyama (1920-73). Yonetani's daily commute to the campus took him through the major railway hubs of Shinjuku and Shibuya, and these became his settings of choice. Unlike most Nihonga painters, Yonetani did not do pastoral landscapes or portraits of individual subjects. Instead he painted the metropolis at its most bustling, and most alienating. His commuters bunch together on train platforms or hustle over crosswalks, the men all in black, the women marginally more colorful in patterned dresses. They stand in formation speaking into rows of pay phones, or line up to do calisthenics in city parks. Yonetani's subjects are never alone, yet each is isolated. In these mass portraits, nobody is interacting with anyone else -- and that is exactly what Tokyo is like during commuting hours.

|

|

Telephones (1982), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 178 x 220 cm; collection of Saku Municipal Museum of Modern Art. |

One of the most intriguing, and poignant, aspects of Yonetani's work is his treatment of the faces in these crowds. On the one hand, they are all of a type; he does not attempt to give each person a distinct identity. Yet we can detect something of their personalities through subtle differences in facial expression or posture (see Last Train I for a revealing study of four passengers). Above all, however, Yonetani is a student of humans engaged in collective motion. In Shinjuku Platform 5, the three people with their backs to us are in funereal black, but their relaxed body language suggests they are somehow removed from the rush-hour crush. The commuters facing us in the throng on the opposite platform, though dressed more colorfully (not a single black overcoat), appear bleak and beleaguered. In his preface to the exhibition catalogue, the artist explains that the titular platform was for long-distance trains -- in other words, the three in the foreground are heading back to their hometowns in the provinces. It is a conscious study in contrasts between the rural Japan of the past and a Tokyo that embodies the country's present and future.

|

|

Last Train I (1971), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 170 x 220 cm. |

Yonetani was fascinated by the ceaseless change in Tokyo's cityscape, which was particularly pronounced around the Shibuya and Shinjuku terminals. Arriving in the capital at the height of the economic boom of the sixties, he was witness to a mind-numbing pace of development that continued more or less unabated for several more years. Shibuya, as depicted in his panoramic Snowy Day, is a maze of trains, pedestrian bridges, and expressways, all vying for space overhead (even the yellow Ginza Line, nominally a subway, is elevated). Yet the torrent of snowflakes falling past the dark hulk of the highway also evokes a snowy night -- or perhaps a starlit sky -- right out of a classic ukiyo-e.

Rain Falls (1990), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 175 x 227 cm. |

Not only snow but also rain figures largely in Yonetani's urban scenes, particularly those at night when wet pavement haphazardly reflects the light from cars and neon signs. Works like ASPHALT and Rain at Midnight manage to bridge realism and abstraction in their reconstruction of colors and shapes for non-figurative purposes.

ASPHALT (1991), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 181.9 x 455.1 cm; collection of Kariya City Art Museum. |

|

Rain at Midnight (1991), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 182 x 226.4 cm. |

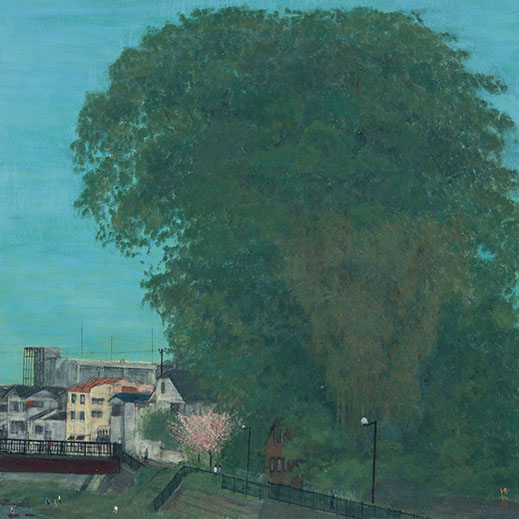

Not long after arriving in Tokyo, Yonetani moved out to the western suburb of Mitaka, where his mentor Yokoyama had a studio. Yonetani fell in love with this bucolic area, where a green belt along a bluff overlooking the Nogawa river preserved something of the prewar rural ambience of the Musashi Plain. For many years he continued to make the long commute downtown through Shinjuku and Shibuya, first to school, then to work. Today, however, he lives in a house/studio overlooking the Nogawa, and his paintings of recent years testify to the inspiration he gains from this environment. In Spring and Spring Before You Know It revel in the lush foliage along the river, celebrating a place that has miraculously escaped -- so far -- the urbanization that encroaches from all sides. Indeed, in his explorations as a Nihonga artist Yonetani seems to have come full circle, to landscapes not unlike those favored by his predecessors.

|

|

In Spring (2001), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 116.7 x 116.7 cm; collection of Mitaka City Gallery of Art. |

Nogawa Park and environs are only a short bus ride from Mitaka Station, where the Mitaka City Gallery of Art is located. Here you can watch egrets and herons in the river, see the Tokyo region's oldest surviving waterwheel in action at an Edo-era grain mill, or tour the verdant grounds of the National Astronomical Observatory. As a matter of fact, you couldn't pick a more pleasant place to spend the afternoon after a visit to the Yonetani exhibition.

Spring Before You Know It (2015), mineral pigment on kumohada mashi, 190 x 380 cm.

|

All works shown are by Kiyokazu Yonetani. All images are courtesy of the Mitaka City Gallery of Art.

|

|

|

| |

5th floor, Coral Bldg., 3-35-1 Shimo-Renjaku, Mitaka City, Tokyo

Phone: 0422-79-0033

Hours: 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. (last entry at 7:30 p.m.)

Closed on Mondays (open on 21 March)

Access: Directly across from the south exit of Mitaka Station on the JR Chuo Line (20 minutes west of Shinjuku, Tokyo), on the 5th floor of the Coral Building |

|

|

| |

|

Alan Gleason

Alan Gleason is a translator, editor and writer based in Tokyo, where he has lived for 30 years. In addition to writing about the Japanese art scene he has edited and translated works on Japanese theater (from kabuki to the avant-garde) and music (both traditional and contemporary). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|